Unabomber's Anti-Tech Revolution: A Critical Analysis (1/2)

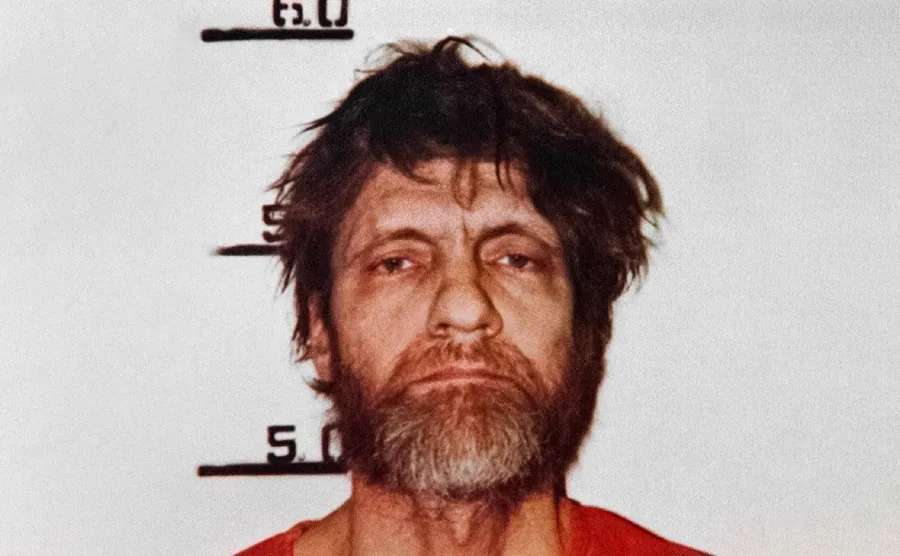

Ted Kaczynski's "Anti-Tech Revolution" challenges the possibility of rationally controlling societal evolution, offering a thought-provoking critique of the complexities and chaotic nature of modern society.

Today, we explore some thoughts on Ted Kaczynski's "Anti-Tech Revolution." Unlike his earlier Manifesto, which reads more like a hurried compilation of ideas (see our post), Anti-Tech Revolution appears to be the product of years of contemplation and systematic reasoning. This should not come as a surprise; Kaczynski completed this book at the age of 72, after spending nearly two decades in prison with substantial access to literature. The book’s refined arguments and coherent logic reveal the mind of someone with a background in mathematics. However, as with his manifesto, we still do not get a clear definition of the technological society against which the book is aimed.

The book is divided into four chapters and several short appendices. The third and fourth chapters focus on revolutionary struggle in general and specifically within the anti-tech movement. While these are interesting, they are less relevant to our work. Instead, we will focus on the first two chapters.

Historical Lessons

The first chapter centers on the assertion that society cannot be rationally controlled, which indirectly challenges the foundation of psychohistory. Kaczynski’s arguments against the possibility of rational social evolution can be grouped into three categories.

The first category draws from historical examples. Kaczynski lists numerous failed legislative attempts to influence society, from ancient Roman laws against luxury to the 20th-century Prohibition in the United States. These efforts, he argues, were at best ineffective and, at worst, led to unforeseen harmful consequences.

However, these examples are not particularly convincing. Firstly, it's not individuals who enact reforms on a whim; instead, these reforms reflect the interests of the societal forces behind them. Kaczynski himself notes, quoting Julius Caesar:

"The higher our station, the less is our freedom of action."

This suggests that these examples do not argue against reform in general, but rather highlight the shortcomings of unilateral policies enacted by specific segments of society for their own benefit. Furthermore, these laws are often not based on scientific reasoning but on a layman's sense of common sense, which almost predestines them to fail. By this logic, past difficulties do not necessitate the abandonment of attempts at rational control but instead call for a more in-depth study of the issue.

Kaczynski's selection of examples is also somewhat one-sided, as one could easily identify instances of successful legislative regulation (albeit sometimes with unexpected consequences). Significant societal achievements include the abolition of slavery, spearheaded by Britain in the 19th century, the establishment of central banks in leading capitalist countries in the first half of the 20th century, and the expansion of rights for women and racial and national minorities over the past century.

It seems somewhat naive to regard successful or failed laws as evidence for or against anything. Laws reflect the struggles of various social groups. If the policies advanced by a particular group align with broader social development, they succeed; otherwise, the law remains ineffective. Moving from "legislative attempts to regulate social life often fail" to "rational control of society is impossible" is not a convincing leap. Rational control would likely not be implemented through administrative actions but rather through the deliberate modification of the conditions in which people live.

It is also worth noting that Kaczynski was a U.S. citizen, a country with one of the highest numbers of lawyers per capita (see here), which might have influenced his thinking.

The Complexity and Chaos of Society

The second line of argument posits that society is complex and chaotic and thus is not predictable and can't be rationally governed. But what do "complex" and "chaotic" mean in this context? A complex system is one that can react unpredictably and cascade to any external influence. The large number of internal elements in the system and even more significant number of connections between them provide this complexity and prevent effective management.

The chaotic nature of the system implies that any linear improvement in predicting its future state requires an exponential increase in the accuracy of the input data about that system. Weather on Earth is an example of a complex, chaotic system. Meteorological forecasts are limited to a few days. To make a reliable forecast for a month, we would need impossibly precise measurements of air temperature and pressure across a vast number of points in space. The Solar System is an example of a relatively simple yet still chaotic system. The planets’ orbits and their positions depend not only on the Sun but also on the other planets, constantly causing perturbations and changes. We can predict the positions of the planets only a few million years into the future. Even if our methods of determining the current positions of the planets were to improve significantly, we could only extend our predictive horizon by a modest amount. As a result, we cannot be entirely sure that the Solar System is stable, meaning it will remain intact as a single unit over the next 10 to 20 million years.

So, is society a complex and chaotic system? We think the answer is both yes and no. It depends on what we mean by society and which of its properties we want to model. There seems to be a substantial space of interesting results that can be obtained by treating society as a simple and deterministic system. We know that population growth on the planet is described by a relatively simple curve. We know that the observed relationship between urbanization and time is also described in a simple manner. The long-term growth of GDP is, in fact, almost linear.

Even if we agree that the system under study is chaotic, this does not mean that, as researchers, we should throw up our hands in despair. The author argues that attempting to make long-term predictions about societal development would require massive computational power and extremely high-quality data collection, but is this necessarily the case? We don’t know what “long-term” means in the context of social systems, so we cannot quantitatively assess the required resources for analyzing the model. For example, if the characteristic time of the system is a human lifespan, then even predictions spanning two or three characteristic times would be considered "long-term" and could have significant practical relevance.

Rational Social Governance: An Impossible Dream?

Suppose we dismiss all historical examples and theoretical considerations and agree that rational control of society is possible. In the third category of arguments, Kaczynski discusses the challenges in implementing such control.

Every person has their own will and a desired direction for societal change. The sum of these wills will not be equal to any single component, meaning no individual will be able to achieve their goal. As Caesar’s quote illustrates, even a despotic ruler finds themselves constrained in their actions. Thus, while control might be theoretically possible, in practice, it is unattainable for anyone.

Kaczynski suggests that even if we were to create an ideal philosopher-king with absolute power over society, issues regarding their selection, succession, and continuity of policy would inevitably arise. And even if this ruler were immortal, their accumulating life experience would still change them and influence their policies. If this policy is continuously changing, we revert to the original thesis—rational control of society in a pre-determined direction is impossible.

To some extent, we cannot dispute these arguments. For Kaczynski, "rational control of society" seems to boil down to discovering some utopian world view and then steadily moving towards it. We agree that such a view is probably impossible. However, we still believe that the widespread dissemination of knowledge about psychohistorical laws will promote societal democratization and economic prosperity. Politics will shift from emotional games to a discussion of rational alternatives. Populist decisions that offer short-term gains will fall by the wayside in public discourse. The persistence of conflicting groups within society and the need for compromise is not, in itself, a problem.

Even if social control is indeed impossible, psychohistory will remain a powerful method for analyzing the past. It will fully replace history and provide a much deeper understanding of our past.

Part two of our review can be found here.

Comments ()