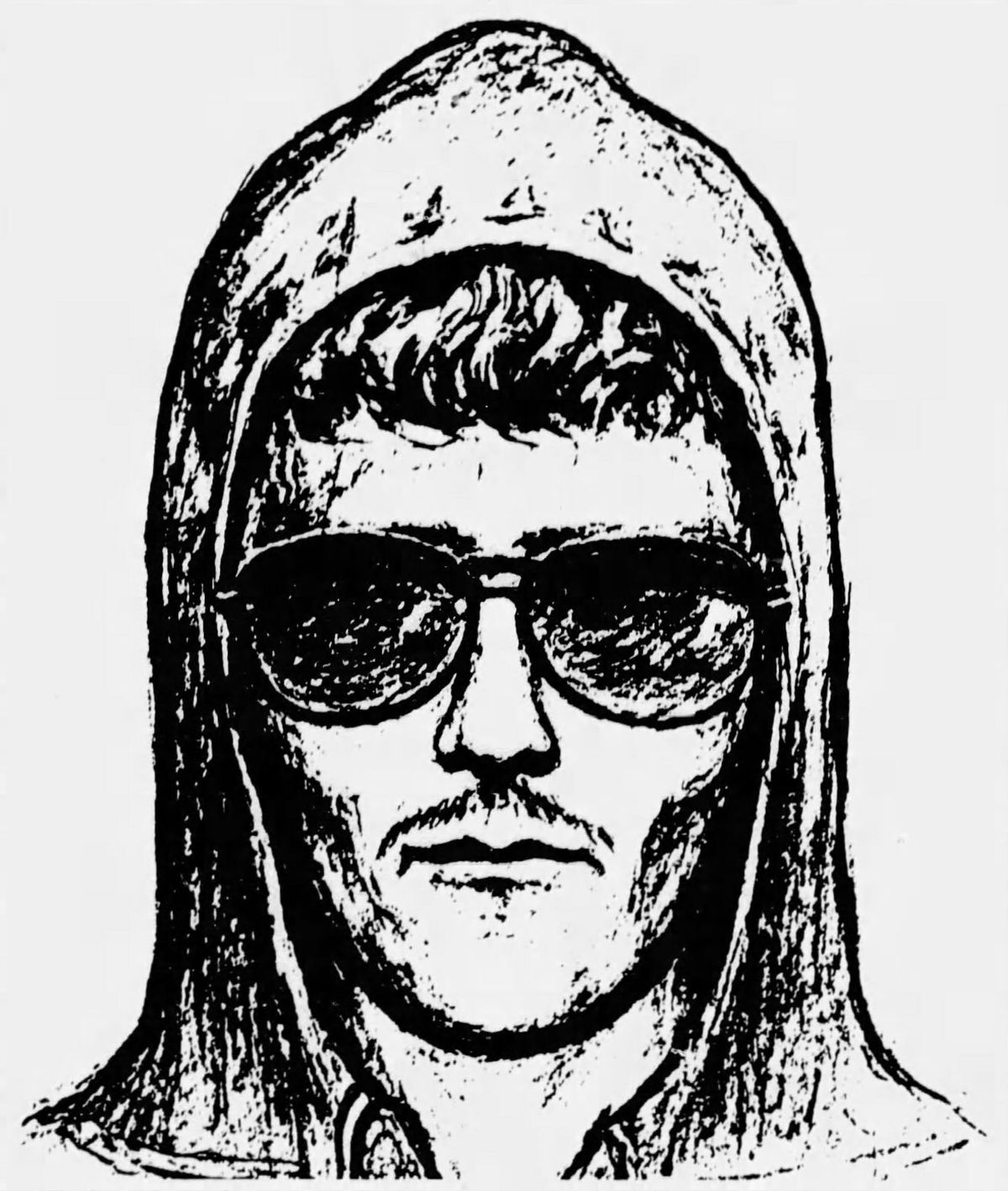

Unabomber Manifesto

Theodore Kaczynski, also known as the Unabomber, a brilliant mathematician, a victim of the MK ULTRA program, an eco-terrorist, and a neo-Luddite, published his manifesto "Industrial Society and Its Future" in 1995 proclaiming imminent collapse of modern civilization.

One of the primary objectives of psychohistory is to predict the future. If the future holds the possibility of a collapse of civilization, then timely response becomes imperative. Theodore Kaczynski, also known as the Unabomber, a brilliant mathematician, a victim of the MK ULTRA program, an eco-terrorist, and a neo-Luddite, published his manifesto "Industrial Society and Its Future" in 1995 proclaiming imminent collapse of modern civilization. The text is readily available online, and hundreds of articles have been dedicated to its analysis. Here, we will highlight some of the ideas presented in the manifesto and provide our perspective on them.

Key Ideas

- A significant portion of the text elaborates on Lenin's thesis that "one cannot live in society and be free from it." It emphasizes the dependency of individuals and their social structures on technology and how technology ultimately defines our way of life. From a psychohistorical perspective, this highlights the pivotal role of technology in shaping societies over time.

- Predicting further technological advancements and the increasing detachment of individuals from the "power process" (a combination of having a goal, the necessary effort to achieve it, and the actual attainment of the goal), the author concludes that there is an impending crisis for industrial society. This crisis could either result in its collapse or lead to the final subjugation of humanity:

...technology is a more powerful social force than the aspiration for freedom. But this statement requires an important qualification. It appears that during the next several decades the industrial-technological system will be undergoing severe stresses due to economic and environmental problems, and especially due to problems of human behavior (alienation, rebellion, hostility, a variety of social and psychological difficulties). We hope that the stresses through which the system is likely to pass will cause it to break down, or at least weaken it sufficiently so that a revolution occurs and is successful, then at that particular moment the aspiration for freedom will have proved more powerful than technology.

- Notably, the concept of a revolution (albeit not a political one) due to the accumulation of mental health problems in society is discussed. This includes the mass use of antidepressants as a method employed by the system to combat these issues.

- The text analyzes the impossibility of a reformist approach to solving the problem of society's interaction with technology and asserts the necessity of a revolution:

Therefore two tasks confront those who hate the servitude to which the industrial system is reducing the human race. First, we must work to heighten the social stresses within the system so as to increase the likelihood that it will break down or be weakened sufficiently so that a revolution against it becomes possible. Second, it is necessary to develop and propagate an ideology that opposes technology and the industrial society if and when the system becomes sufficiently weakened. And such an ideology will help to assure that, if and when industrial society breaks down, its remnants will be smashed beyond repair, so that the system cannot be reconstituted. The factories should be destroyed, technical books burned, etc.

- A significant portion of the manifesto is devoted to critiquing "leftists" in the American sense—those who fight against racism, advocate for women's rights, LGBTQ+ rights, etc. Although the manifesto was written in 1995, this critique appears remarkably relevant in 2023. However, its connection to the main theme of the text is debatable.

Our Critique

- In the text dedicated to criticizing technology and industrial society, authored by a professional scientist, there's a notable absence of a clear definition of these terms: technology, industrial society, and the frequently mentioned "system." This omission, strictly speaking, calls into question the value of the entire text.

- Many aspects of societal life are presented in the text as worsening trends without substantiation, rather than as phenomena that have existed to some extent throughout history. For example:

And today's society tries to socialize us to a greater extent than any previous society. We are even told by experts how to eat, how to exercise, how to make love, how to raise our kids and so forth.

It's evident that religion also controlled all these aspects of life in e.g. medieval Europe. Similarly, discussions about the desire to be sexual and attractive until old age lack historical context.

- The manifesto mixes ideas about hunter-gatherer and agrarian societies, often unclearly, making it challenging to discern which one is being appealed to as superior.

- Erroneous predictions are made about the replacement of low-skilled labor with machines. In practice, we see an increasing demand for such labor, while machines are replacing medium-skilled workers.

- The out-of-place attacks on regimes declared as dictatorial by the United States seem somewhat amusing and narrow-minded in the context of the manifesto's broader scope, suggesting the limited perspective of the author.

- Ultimately, Unabomber criticizes technological society for imposing too many restrictions on human freedom. However, doesn't the biosphere itself impose similar limitations? If one takes creationist positions and regards the biosphere as artificial in some sense, what exactly distinguishes the technosphere from the biosphere?

Comments ()