The DNA Behind Your Ability to Argue on the Internet

FOXP2: The Source of All Voices

What Makes Us Unique?

What if the essence of what makes us human — our ability to craft stories, debate ideas, or whisper “I love you” — is partly written in our DNA? Enter FOXP2, a gene shrouded in scientific intrigue and poetic possibility. Dubbed the “language gene,” FOXP2 doesn’t hold all the answers to human communication, but it offers a tantalizing glimpse into how biology and evolution conspired to give us the gift of speech. This is the story of how a single gene, discovered in a family struggling to speak, reshaped our understanding of what it means to be human.

The Discovery: A Family’s Struggle and a Scientific Breakthrough

In the 1990s, a British family known as the KE family became unintentional pioneers in genetics. Half of its members faced profound speech and language challenges: they stumbled over grammar, struggled to articulate words, and even had difficulty coordinating facial movements for simple tasks like blowing out a candle. For years, their condition was a mystery — until geneticists identified a culprit: a mutation in FOXP2, a gene on chromosome 7.

This discovery was groundbreaking — the first time a specific gene was linked to speech and language. But FOXP2 wasn’t just a human curiosity. Scientists soon found it in creatures as diverse as mice, bats, and songbirds, hinting at its ancient role in communication long before humans walked the Earth.

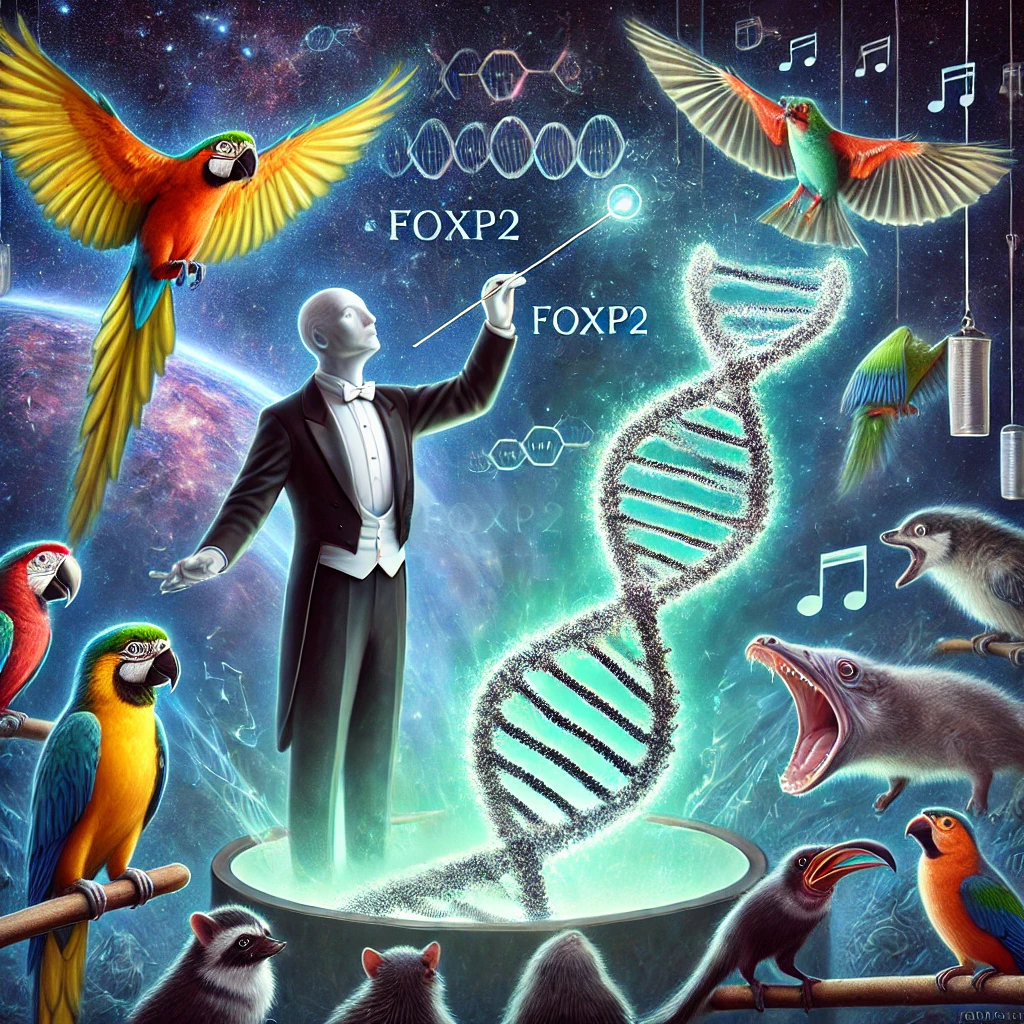

What Does FOXP2 Actually Do? The Conductor of the Genetic Orchestra

FOXP2 isn’t a solo performer; it’s a *transcription factor*, a molecular conductor that orchestrates the activity of hundreds of other genes. In the brain, it plays a critical role in shaping circuits involved in speech, language, and even fine motor skills. Key brain regions under its influence include: the basal ganglia (a deep-brain structure that helps coordinate movement) and the cortex (the brain’s outer layer, where complex language processing occurs). We can think of them as the rhythm section and the lead singer of our neural band.

When FOXP2 malfunctions, as in the KE family, the consequences ripple widely. Synaptic plasticity — the brain’s ability to rewire itself through learning — is impaired. This explains why language, a skill honed through practice and repetition, becomes an uphill battle.

Evolution’s Tiny Tweaks: How FOXP2 Shaped Humanity

Humans and chimpanzees share over 98% of their DNA, but FOXP2 carries two critical amino acid changes that set our version apart. These tweaks likely emerged over 500,000 years ago — and intriguingly, Neanderthals and Denisovans shared the same human-like FOXP2. Did they have language? We may never know, but their genetic legacy suggests the roots of communication run deep.

In 2009, scientists conducted an experiment worthy of a horror movie: they inserted the human version of the FOXP2 gene into mice. The results were unexpected. The rodents did not speak (fortunately for our kitchens), but their squeaks in the ultrasonic range — the way they communicate with their relatives — have changed. Moreover, the mice began to find their way out of the maze faster. It turned out that FOXP2 affects not only speech, but also cognitive abilities.

And now — to romance. Zebra finches, birds whose mating serenades are learned from youth, lose their talent for singing if FOXP2 breaks down. Their songs become a cacophony, as if Spotify had accidentally mixed Metallica tracks and lullabies. This discovery showed that the gene is critical for learning complex sound patterns — be it human speech or a bird’s love song.

FOXP2 is not exclusive to humans. It is present in all vertebrates, and plays a role everywhere:

i) Birds use it to imitate sounds (parrots, by the way, are also in the club).

ii) Bats use the gene for echolocation — their “sonar” calls require incredible precision.

iii) Toadfish (yes, there are such) emit beeps to attract mates, and FOXP2 helps them to be on point.

This calls into question the idea that the gene is “made for speech.” Rather, it is part of an ancient mechanism that evolution has adapted for different forms of communication.

It was long thought that the human version of FOXP2 had undergone “accelerated” evolution, becoming the basis for our linguistic superiority. But in 2018, DNA analysis dispelled this myth: no traces of recent positive selection were found in humans. In fact, one of the two amino acid differences between us and chimpanzees arose independently in… predators and bats.

It’s like discovering that beavers also mix Bellinis. Evolution, apparently, likes to repeat successful solutions.

If FOXP2 is present even in mute fish, why do its mutations in humans cause severe speech and language comprehension disorders? The answer is in context: the gene does not work alone. It is the conductor of an orchestra of hundreds of other genes that regulate the development of neurons, synapses, and even the motor skills of the mouth muscles.

In humans, a breakdown of FOXP2 is like knocking down the first domino: the entire system collapses. In birds, the fall of another domino only affects songs. Therefore, to say that FOXP2 is a “language gene” is like calling a wheel a “travel gene”: without an engine, roads, and the desire to move, it is useless.

Now to the controversial. A 2018 study showed that in 4–5 year old girls, FOXP2 is 30% more active in Broca’s area (the area of the brain associated with speech) than in boys. The authors cautiously suggested: “Perhaps this explains why women are more verbal.” Of course, here I want to insert a joke about “nature, which knew that girls need to discuss everything from dinosaurs to the meaning of life back in kindergarten.” But science reminds us: correlation ≠ causation. Maybe girls just practice speech more often, activating the gene? Or has evolution really built a “chat module” into us? The debate remains open, as does the question of why scientists are still looking for biological explanations for gender stereotypes. My humble opinion is that it is not women who are more verbal, but men who are more leisurely.

All these facts suggest FOXP2 didn’t “invent” language but refined neural circuits that allowed complex communication to flourish in humans. Evolution, it seems, reused an ancient genetic tool for a revolutionary new purpose.

Still, FOXP2 is no “master gene.” Language disorders arise from a symphony of genetic, environmental, and epigenetic factors. As geneticist Simon Fisher notes, “FOXP2 is a window into the biology of speech — not the whole house.”

The Future: Editing Genes, Growing Brains, and Ethical Dilemmas

Today, scientists are probing FOXP2 with tools that sound like sci-fi:

- CRISPR-edited animals;

- Brain organoids: miniature, lab-grown brain models show how FOXP2 shapes developing neural networks.

- Ancient DNA: sequencing Neanderthal genomes raises provocative questions: Could they speak? Did they sing?

But with power comes responsibility. Could editing FOXP2 enhance human cognition? Should we “fix” genetic differences tied to identity? These questions linger as science races forward.

FOXP2 teaches us that language is neither simple nor solitary. It’s a masterpiece composed by evolution, conducted by genes like FOXP2, and performed by the brain’s intricate circuits. Yet, it’s also a skill sculpted by culture, learning, and the stories we pass down.

As we unravel the genetic threads of speech, FOXP2 challenges us to stay humble. After all, our ability to debate, dream, and connect — to shout into the void and hear an echo — is a miracle written in DNA, shaped by millennia, and still being decoded.

What other secrets lie hidden in our genes? The next chapter awaits

Further Reading:

- The Language Instinct by Steven Pinker (a deep dive into the biology of communication)

- Neanderthal Man: In Search of Lost Genomes by Svante Pääbo (explores ancient DNA and human evolution)

- FOXP2: A Window into the Genetics of Speech (Nature Reviews Genetics, 2019)

What do you think — could genes like FOXP2 redefine how we see ourselves? Share your thoughts in the comments.

Comments ()