Sex Is a Team Sport

We explore the remarkable diversity of human family forms

Disclaimer:

This article examines family structures from an evolutionary perspective, focusing on types of families historically capable of producing offspring prior to the development of modern reproductive technologies. However, the title “Sex is a team sport” applies to all forms of family and partnership, regardless of gender identity, sexual orientation, or preferences. Our goal is to explore evolutionary aspects, not to limit the concept of family to contemporary definitions.

In contemporary societies, serial monogamy has emerged as one of the predominant patterns of interaction between genders. It can be described as a series of relentless attempts to find "the one" — a lifelong partner — through successive monogamous relationships. However, modern society also recognizes a wide variety of relationship structures and partnerships that reflect diverse preferences, identities, and cultural norms.

It is particularly fascinating to explore how many traditional societies operate under fundamentally different values and relationship frameworks. These alternative systems often reflect adaptations to historical, ecological, and social conditions that shaped human relationships long before the dominance of serial monogamy. Understanding these diverse approaches can offer valuable insights into the evolutionary and cultural roots of human family structures.

Polyandry: a unique adaptation of family structures

Polyandry is rare, but represents a unique adaptation to harsh environmental and social conditions. The practice is most prominent in Tibet, Nepal, and parts of India such as Ladakh. Most often, polyandry takes the form of one woman marrying multiple brothers. This structure avoids the fragmentation of land plots among heirs, maintaining the integrity of the household, which is vital in resource-poor settings. Instead of dividing the family, the brothers work together to maintain the household, with the woman acting as a coordinator, pooling their efforts. Similar examples are found in other parts of the world. In parts of the Amazon and among peoples of southern India such as the Toda, polyandry was also associated with social and economic stability. A woman with multiple husbands ensured protection and shared labor. In Africa and Polynesia, polyandry was rare, but was sometimes practiced in temporary unions, especially to strengthen social ties between clans or groups. Often, such marriages were a practical decision rather than a romantic choice. Today, polyandry is gradually disappearing, giving way to monogamous marriages. Urbanization, education, and marriage laws are changing traditional ways. However, in remote areas, such as the Himalayan mountains, practice still exists. It reminds us that marriage traditions are not only a reflection of culture, but also a pragmatic strategy for survival in difficult conditions.

Life in Tibet and Nepal is not a bed of roses. This is not the life of the capital with its complaints about traffic jams and hot water outages. The land here is as harsh as the air, soaked in snow and cold. Tiny fields are all a family has. Divide them among several sons, and you get poverty and hunger. That is why brothers not only are friends, but also marry the same woman. This is not debauchery, this is an economic model where everyone takes on a role that matches their strengths.

Let's not be hypocrites. It does not matter whose child it is. What matters is that he is fed, warmed, and has a future. In other words, they solve their problem in a way that we, smart guys with our divorce proceedings, do not always manage.

Polygamy: a tradition of survival and status

Polygamy, or polygyny, is a family structure in which one man is married to multiple women. The practice is widespread in Africa, the Middle East, and parts of Asia, where it plays an important role in economic and social stability. In these societies, polygamy allows wives to pool their efforts in running the household, raising children, and sharing household chores. A man who is able to support multiple wives often gains high social status, making polygamy a symbol of success and influence.

Historically, polygamy arose as a practical solution to the high mortality rate of men due to war, hunting, or hard labor. For example, among the Masaai tribes of East Africa, polygamy helped compensate for the imbalance between the number of men and women. In addition, in Islamic societies, polygamy is regulated by religious prescriptions: the Quran allows a man to have up to four wives if he is able to provide for them equally. In such cultures, this is perceived not as oppression, but as responsibility.

Look at the root. In societies with polygamy - and this is Africa, the Middle East, Central Asia - it's all about survival. A man who has several wives primarily solves two practical problems: increasing the size of the family and economically strengthening the home.

For example, among the Masaai in Kenya, one wife looks after the cattle, another raises the children, and the third does the housework. All the roles are distributed, and, oddly enough, this brings order. And the children? There are more of them than a European with his one-room apartment with a mortgage, and each pair of hands is worth its weight in gold.

A fairy tale about harmony? Polygamy is a harmonious structure, but women's happiness, alas, is far from always a priority.

Polyamory and equality in ancient polynesian and amazonian cultures

Ancient Polynesian cultures such as the Marquesas Islands and some Amazonian tribes had unique systems where relationships between men and women were built on the principles of equality and polyamory. In the Marquesas Islands, for example, before the arrival of Europeans, sexual freedom was a natural part of life. Women and men could have multiple relationships both before and after marriage without experiencing social condemnation. This was due to the fact that inheritance of land and property occurred through matrilineal lines, and social status was determined more by a person’s contribution to the community than by marriage.

In the Amazonian forests, tribes such as the Bare and Canelos had the concept of “multiple paternity.” It was believed that a child could inherit the qualities of all the men with whom his mother had relationships. This strengthened the social bonds between men and ensured that the child had multiple protectors and providers. In these societies, men were also able to have relationships with multiple women, which was seen as part of their role in strengthening the community. This freedom in choosing partners maintained balance and eliminated jealousy, as attention was distributed equally and responsibility for the family was shared among all participants.

Both of these cultures demonstrate that equality in relationships and freedom to choose partners can exist without destroying the social structure. In them, family structures were flexible and adaptive, focused on community harmony and collective responsibility for children. Modern ideas about equality and polyamory can draw inspiration from these ancient practices, where mutual respect, cooperation, and free choice of partners were key principles.

Equality and monogamy in traditional cultures

In a number of traditional cultures around the world, monogamy is combined with principles of equality, where men and women participate equally in decision-making, housekeeping, and child-rearing. Such societies demonstrate that stable relationships can be built on partnership rather than on a strict division of gender roles. Examples of such cultures are the San (Bushmen) peoples of South Africa, as well as the Sami, the indigenous peoples of Scandinavia and the Kola Peninsula.

For the San, who live as hunter-gatherers, monogamy is a natural form of relationship, as it ensures the stability of the group and the equal distribution of resources. Men hunt, and women gather roots, berries, and edible plants. However, their contribution to the general well-being of the community is valued equally. Decisions concerning the family are made jointly, and children are raised by the entire community, which reduces the burden on one of the partners. Respect for the work of each makes equality the basis of their lives.

The Sami, traditional nomads of Scandinavia, also build their families on equal principles. Women take part in caring for the reindeer and processing their products, while men perform the physically demanding tasks associated with nomadic life. Monogamous marriages among the Sami are not only a union of two people, but also a partnership, where everyone plays an important role in maintaining the household. Their way of life emphasizes mutual respect, collectivism, and flexibility in the distribution of responsibilities, which makes monogamy a natural choice.

Conclusion

These examples show that equality in monogamous traditional cultures is based on pragmatism and respect for the work of all family members. Such societies serve as a reminder that partnership and shared responsibility are universal principles that can ensure stability and harmony in any environment.

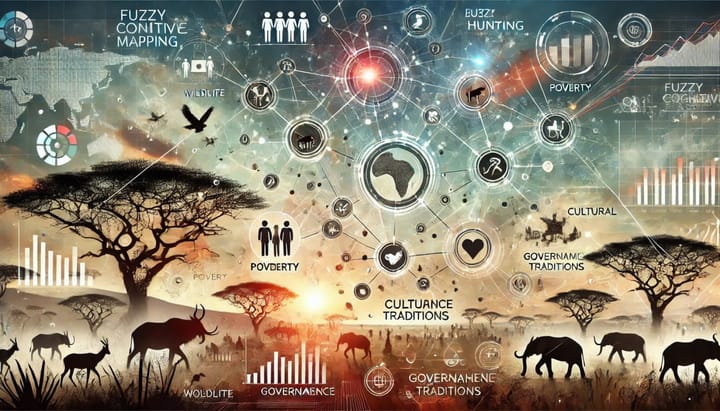

The diversity of human family forms is remarkable and often shaped by adaptations to specific ways of life. Whether influenced by ecological, economic, or social factors, family structures reflect the flexibility and ingenuity of human relationships. Interestingly, similar patterns can be observed in the animal kingdom, where many species also display consistent tendencies in forming family units.

This raises a compelling question: is our inclination toward particular family models dictated by societal traditions, or is it rooted in our biochemistry? In the next article, we will explore the biochemistry of fidelity using examples from the animal world, shedding light on the evolutionary and chemical foundations of commitment and partnership.

Comments ()