New Moon Race

It has been over 50 years since the last human set foot on the Moon, but Earth's only natural satellite has once again captured the attention of major world powers. How did this come about, and what can we expect in the future?

It has been over 50 years since the last human set foot on the Moon, but Earth's only natural satellite has once again captured the attention of major world powers. How did this come about, and what can we expect in the future?

Motivation and Opportunity

While the Moon is significantly smaller than Earth, its surface area is still larger than Africa's. In terms of its chemical composition, it is relatively similar to Earth. Given that its resources have never been exploited by humans, we can hope to find easily accessible deposits of many valuable minerals on its surface. Already, titanium ores 10 times richer than Earth's have been discovered, and there are expectations of deposits of gold and silver dust in polar regions. We must not disregard the potential for access to cheap energy sources too, both solar and geothermal (or selenothermal?).

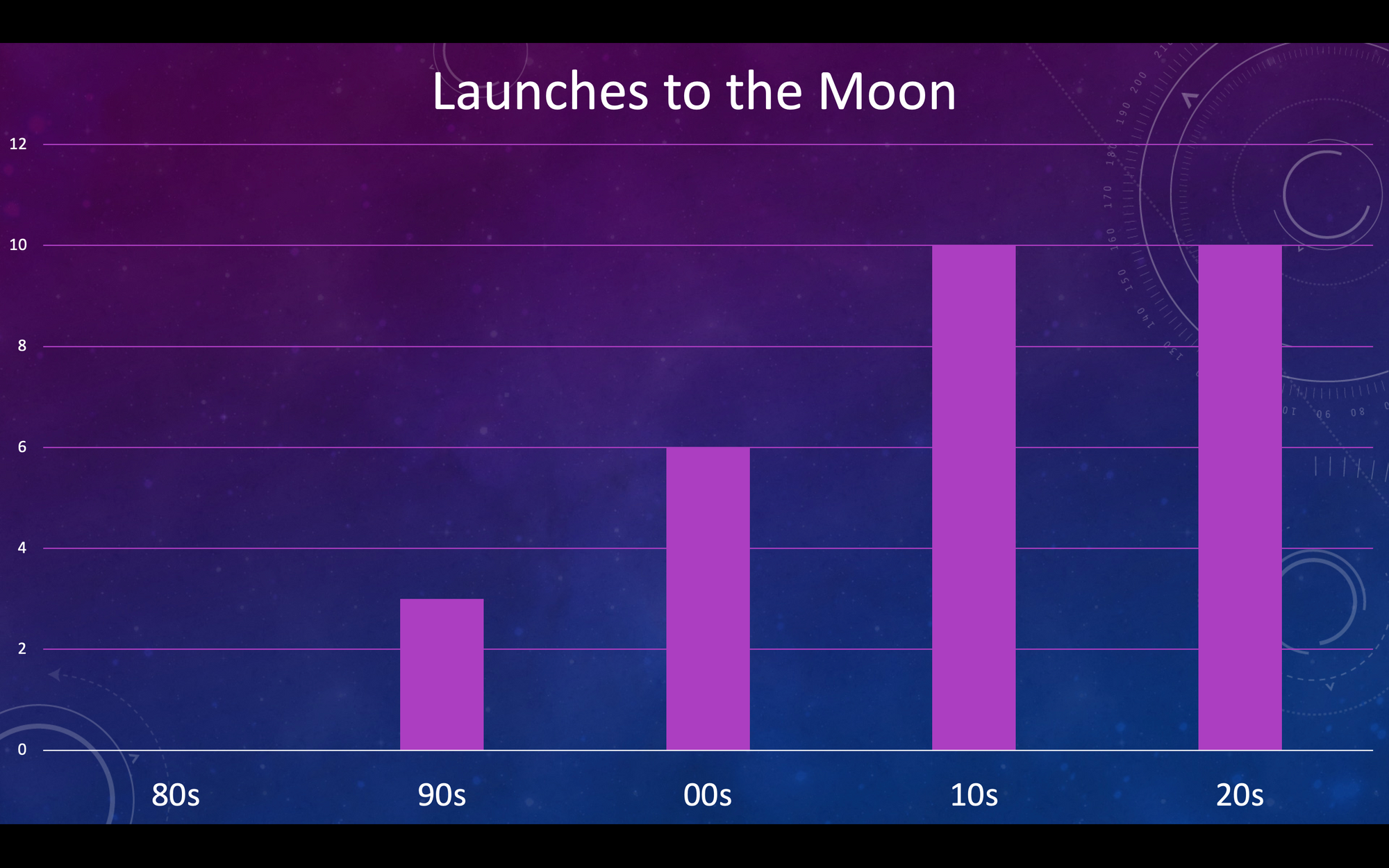

All of this was known since the time of the first space race when the United States and the Soviet Union, competing for dominance, conducted extensive lunar research in a short period. Nevertheless, after the last landings by the United States in 1972 (the manned Apollo 17 mission) and by the Soviet Union in 1976 (the Luna 24 robotic mission), interest in the Moon waned. In the 1980s, there was not a single research mission to the Moon.

Over time, scientific interest began to rekindle, culminating in the discovery of water on the Moon by the Indian spacecraft Chandrayaan-1 in 2009. It turned out that a significant amount of water had accumulated in permanently shadowed regions of the lunar surface. This water is not only necessary as part of a life support system but also serves as raw material for producing hydrogen-oxygen propellant. This means that the mass of cargo required to be sent to the Moon to create and sustain a colony has significantly decreased.

Rocket technology has also made significant progress over the past 50 years. If the Apollo program required the United States to spend around 4-5% of the federal budget, a similar modern program like Artemis consumes less than 0.5%. Advances made by SpaceX and other companies in reusable rockets are not yet being utilized, although they are likely to further reduce the cost of launching payloads into orbit.

As of today, the necessary combination of motivation (acquiring and exploiting resources) and opportunity (detecting water and reducing logistics costs) for starting lunar colonization has developed, or is nearly there. In just the last three years, various degrees of successful lunar missions have been carried out by China, the United States, Japan, India, South Korea, the United Arab Emirates, and Russia.

Scramble for the Moon

Let's go back 170 years. Starting around 1850, Europeans began mass-producing and using quinine, a medicine to combat malaria. Africa, previously largely inaccessible to white people (Europeans controlled less than 10% of the continent, mostly along the coast), opened its doors, promising vast wealth and new markets.

The political framework for the scramble for Africa was established at the Berlin Conference of 1884. To determine which nation had a claim to a colony, the principle of effective occupation was developed: a European nation could only claim rights to the land if it could support its presence with its own flag, administration, military forces, or at least agreements with local leaders. Could something similar happen on the Moon?

Currently, the Outer Space Treaty, developed during the first space race and signed by most countries in the world, is in effect. It includes some of the following crucial provisions:

Article I. ... Outer space, including the moon and other celestial bodies, shall be free for exploration and use by all States without discrimination of any kind, on a basis of equality and in accordance with international law, and there shall be free access to all areas of celestial bodies. ...

Article II. Outer space, including the moon and other celestial bodies, is not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means.

The treaty does not explicitly prohibit resource mining on the Moon, laying the foundation for potential future conflicts.

In 2017, the United States initiated the Artemis program, aiming to return humans to the Moon. Three years later, in 2020, they introduced the Artemis Accords, a set of international cooperation rules that foreign states must sign if they wish to participate in the Artemis program. These accords do not explicitly contradict the Outer Space Treaty but introduce a new concept of "safety zones":

Section 11.7 In order to implement their obligations under the Outer Space Treaty, the Signatories intend to provide notification of their activities and commit to coordinating with any relevant actor to avoid harmful interference. The area wherein this notification and coordination will be implemented to avoid harmful interference is referred to as a ‘safety zone’. A safety zone should be the area in which nominal operations of a relevant activity or an anomalous event could reasonably cause harmful interference. The Signatories intend to observe the following principles related to safety zones:

(a) The size and scope of the safety zone, as well as the notice and coordination, should reflect the nature of the operations being conducted and the environment that such operations are conducted in;

(b) The size and scope of the safety zone should be determined in a reasonable manner leveraging commonly accepted scientific and engineering principles;

(c) The nature and existence of safety zones is expected to change over time reflecting the status of the relevant operation. If the nature of an operation changes, the operating Signatory should alter the size and scope of the corresponding safety zone as appropriate. Safety zones will ultimately be temporary, ending when the relevant operation ceases;...

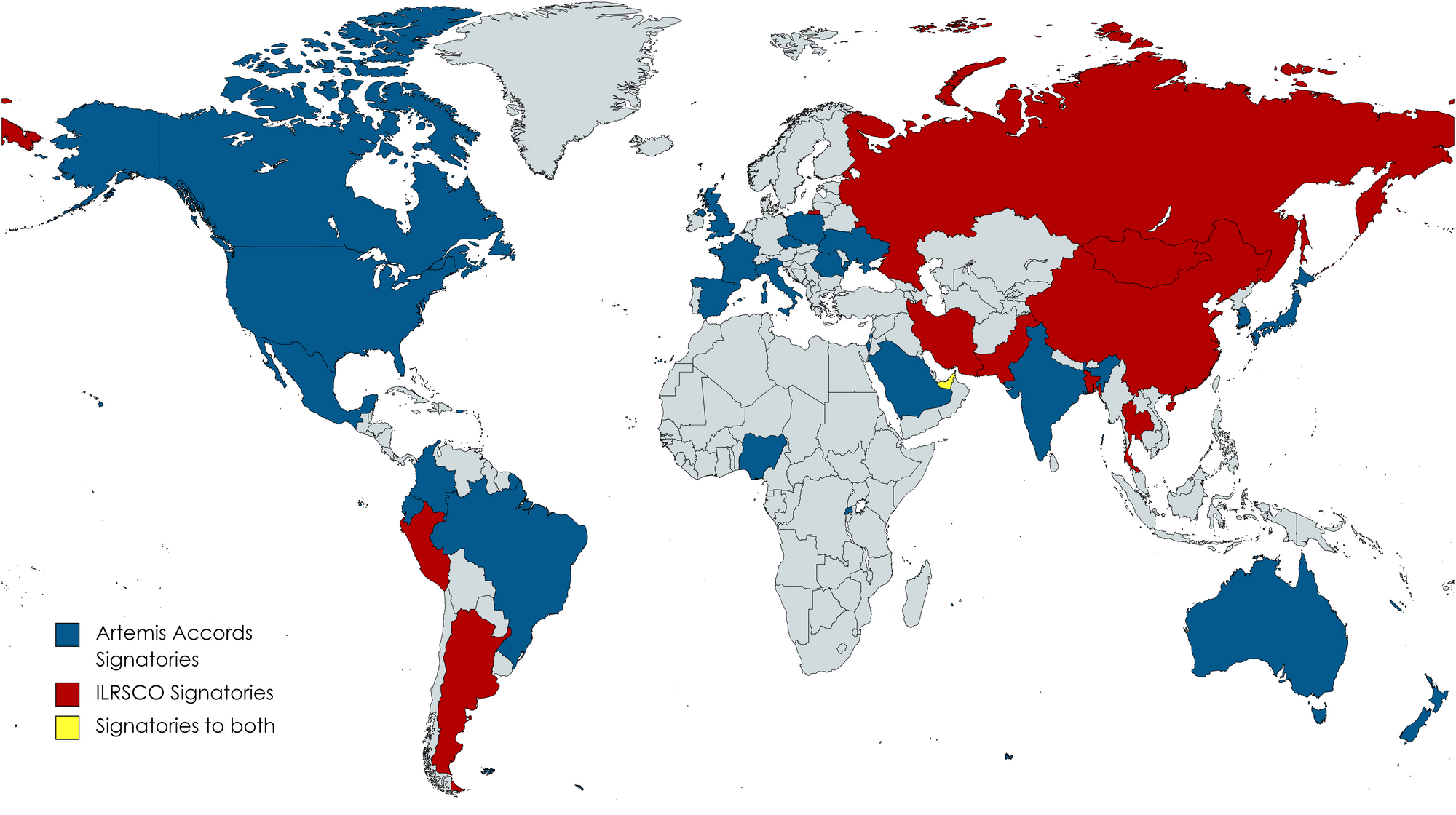

Many friendly and U.S.-dependent nations have already signed these Accords, while China has initiated its own international lunar exploration program, with support from Russia and a small number of other countries.

We believe that the so-called "safety zones" essentially revive the principle of effective occupation and, in substance, violate the spirit of the Outer Space Treaty. The Artemis Accords resemble a new Berlin Conference, and it took less than 30 years from the conclusion of the original Berlin Conference to the near-complete division of Africa among major powers. We will soon see how long it takes for the new scramble for the Moon.

P.S. We do not know if lunar resource mining will be economically justified when Earth still has unexplored oceans and Antarctica. Continuing the analogy with Africa, we only remind you that most European colonies turned out to be unprofitable and "useless," which did not affect the speed or completeness of the continent's division. The fear that a rival will capture something valuable compels all participants to assert their rights to as much land as possible as quickly as possible.

Comments ()