From Martian Sands to Arctic Myths

How our brain seeks order in chaos

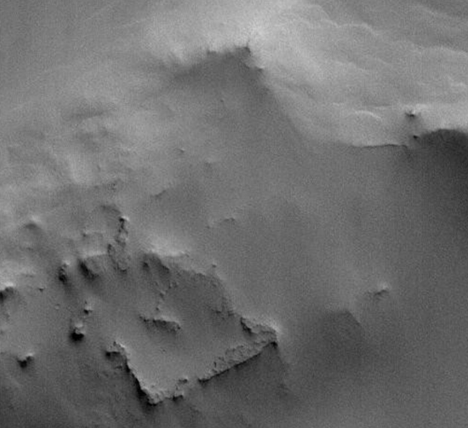

A new NASA image reveals a strange rectangular structure on the Red Planet. The ruins of an ancient civilization? An optical illusion? Or just another trick of our brains? Let’s find out.

Lost in Translation

Mars has always played tricks on us. It still does.

In 1877, Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli peered through his telescope and saw something strange — thin, dark lines crisscrossing the Martian surface. He called them canali — the Italian word for “channels” or “gullies.”

Schiaparelli never claimed these lines were artificial. But something got lost in translation. When canali reached English-speaking scientists, the word became canals — a term that implied intelligent design.

That single mistranslation changed everything. American astronomer Percival Lowell seized the idea and ran with it. Convinced that Mars was home to a dying civilization, he spent years mapping these so-called canals. In 1894, he built an entire observatory just to study them.

He wasn’t alone. Other astronomers, eager to confirm the existence of canals, also began “seeing” them through their telescopes. Each new observation seemed to reinforce the previous ones. The canals became a self-sustaining idea — one expert’s certainty fueling another’s. Of course, not everyone was convinced. Skeptics pointed out inconsistencies, but their voices were drowned out by the enthusiasm of those who believed Mars was inhabited.

His books, like Mars and Its Canals (1906), painted a vivid picture: an ancient, intelligent race battling extinction, constructing vast waterways to transport water from the ice caps to the dry equatorial plains.

The world was mesmerized. Newspapers, science fiction writers, and even scientists fell under the spell. The idea of a once-thriving Martian civilization became so popular that it burned itself into our collective imagination — fueling decades of speculation, novels, and alien myths.

But there was a problem. The canals weren’t real.

Early photographs of Mars and observations with better telescopes showed no canals, only rough, cratered terrain. Scientists realized that the human brain tends to connect random dots into patterns — a psychological illusion known as pareidolia.

The Martians we imagined? They had never existed.

Lowell always insisted that the regularity of the canals was an unmistakable sign that they were of intelligent origin. This is certainly true. The only unresolved question was which side of the telescope the intelligence was on.

— C. Sagan Cosmos

Cydonia Pyramids

By the time we reached the Space Age, Martians had returned — this time not as canal builders, but as architects of colossal monuments.

On July 25, 1976, NASA’s Viking 1 orbiter snapped a photograph of the Cydonia region on Mars. Among the craters and hills, one formation stood out: a 300-meter-tall mesa that, under the right lighting, bore an uncanny resemblance to a human face. It had “eyes,” a “nose,” a “mouth.” And it wasn’t alone — nearby, other rocky formations were quickly interpreted as pyramids and the ruins of an ancient city.

NASA scientists immediately noted that the “Face” was likely a trick of light and shadow, exacerbated by the low resolution of the camera (one pixel equaled 50 meters). But their cautious skepticism was no match for public imagination. The official NASA press release described the formation as a “huge rock formation… resembling a human head,” and that single phrase ignited a firestorm of speculation.

The image spread like wildfire. Newspapers, TV specials, and books seized on the idea that this could be evidence of an ancient Martian civilization — one that may have even influenced Egypt’s pyramids. Enthusiasts pointed to mathematical alignments, supposed structures, and “anomalies” in Cydonia as proof that Mars was once home to an advanced race.

The “Face” became a pop culture icon. It appeared in films, TV shows, video games, and music. Theories ranged from lost civilizations to alien intervention in human history. Was Mars once home to an intelligent species? Had they built pyramids? Had they somehow contacted Earth?

Then, in 1998 and 2001, NASA sent back new images. This time, the resolution was far sharper — just 4–5 meters per pixel. The truth was inescapable.

The Face was just a mesa — a flat-topped hill, sculpted by wind and erosion. Under different lighting conditions, the illusion disappeared, revealing nothing but a rugged, chaotic landscape.

In Search of Hyperborea

Mars isn’t the only place where our minds see lost civilizations in stone. One of the article’s authors had the fortune of participating in an expedition during her teenage years to search for traces of ancient Hyperborea along the shores of the White Sea. It can be confidently stated that the process of identifying and selecting megalithic features involved a certain flight of imagination: any stone that could be interpreted as a trace of an ancient civilization was immediately labeled as such.

Another key insight drawn from the expedition was the selectivity of human vision. Along the coastline and within rock formations, our eyes instinctively seek out familiar patterns — primarily human faces. When this trait is combined with the mythological mindset of prehistorical inhabitants of these lands, it becomes clear how myths of stone giants and merciless deities arose. The stones, shaped by nature, became canvases for projecting beliefs, fears, and the human need to find meaning in chaos.

Photo from the author’s personal archive: “Throne of the Hyperborean Queen” — a massive stone weighing several tons, lifted by expedition members and two jacks.

Photo from the author’s personal archive: “Visage of Odin” — a rock formation interpreted as bearing the mythical likeness of the Norse god, its weathered contours evoking the one-eyed deity’s gaze.

Cognitive Origins of Illusion

Imagine: you’re walking along a seashore, pick up a stone — and suddenly notice it’s strikingly similar to a human face. Or you gaze at photos of Martian landscapes and spot a “statue” or a “tower”… Why does our brain so insistently transform chaos into order, randomness into meaning? This is no glitch. It’s ancient code hardwired into our neural architecture.

We are a species that survived thanks to paranoia. Our ancestors couldn’t afford doubt: Was that rustle in the grass the wind or a predator? Better to err and flee than become prey. The brain evolved to detect patterns instantly, even at the cost of false alarms. Regions like the fusiform gyrus, responsible for facial recognition, fire at the slightest hint of familiar features — this is how pareidolia arises. We see faces in clouds because our social brain is wired for it.

But it’s not just evolution. Our perception is a dialogue between the world and an internal library of images. Gestalt principles, as described by psychology’s pioneers, are rules by which the brain “completes” reality. If an object resembles an arch, a cup, a figure — neurons finish the shape like an artist adding the final stroke. Here lies the trap: the brain doesn’t distinguish “similar” from “is.” It trusts its illusions, born of its own optimization.

Culture and personal experience add layers. A religious person sees a saint’s visage in a wall stain; an archaeologist, an artifact in an ordinary stone. This isn’t deception but a projection of inner narratives. The brain is a master storyteller: it takes reality’s raw material and wraps it in the film of our expectations.

Why does this matter? Because here, neuroscience and philosophy collide. We are creatures incapable of living in chaos. Even an infant seeks its mother’s face, not random light patterns. Our minds cling desperately to meaning, like a climber gripping a cliff’s ledge — sometimes grasping mirages.

This mechanism gifted us art, science, metaphors… and cruel delusions. The same algorithm births both genius insights and conspiracy theories. We pay for our creativity: a brain that sees constellations in starry chaos just as easily turns shadows into monsters.

Comments ()