Are Nobel Laureates Noble?

Science is not without borders

As Nobel Prize week has just concluded, it's an opportune moment to reflect on what an analysis of hundreds of laureates can reveal about the structure of modern science. It turns out that the world of scientific excellence is more exclusive than many might imagine—often resembling a club of the privileged, with many laureates coming from wealthy families. Moreover, who your academic advisor is may play a far greater role in your success than you once thought.

My university English professor often said, "There is nothing noble in getting a Nobel Prize" to highlight the difference in pronunciation between "noble" and "Nobel". But is that really true? Today, we’ll discuss two articles examining Nobel laureates.

Socioeconomic Background

The first article [1] begins with a quote from the famous American biologist and science popularizer Stephen Jay Gould:

I am, somehow, less interested in the weight and convolutions of Einstein’s brain than in the near certainty that people of equal talent have lived and died in cotton fields and sweatshops.

As is often the case with statements made by intellectuals, this one raises ethical questions. Instead of striving to improve the working conditions of people in plantations and factories, it suggests that we should select some individuals based on certain criteria—here, intellect—and "rescue" them for a higher purpose, which is assumed to be inherently noble, namely the advancement of science. However, we digress here; fundamentally, as the research will show, this statement is largely true—a vast amount of intellectual potential remains untapped.

If talent is evenly distributed across the human population, but observed scientists mainly come from a specific subset of that population (for example, specified by income, gender, or nationality), then we can conclude that many gifted individuals remain unnoticed and their talents unutilized.

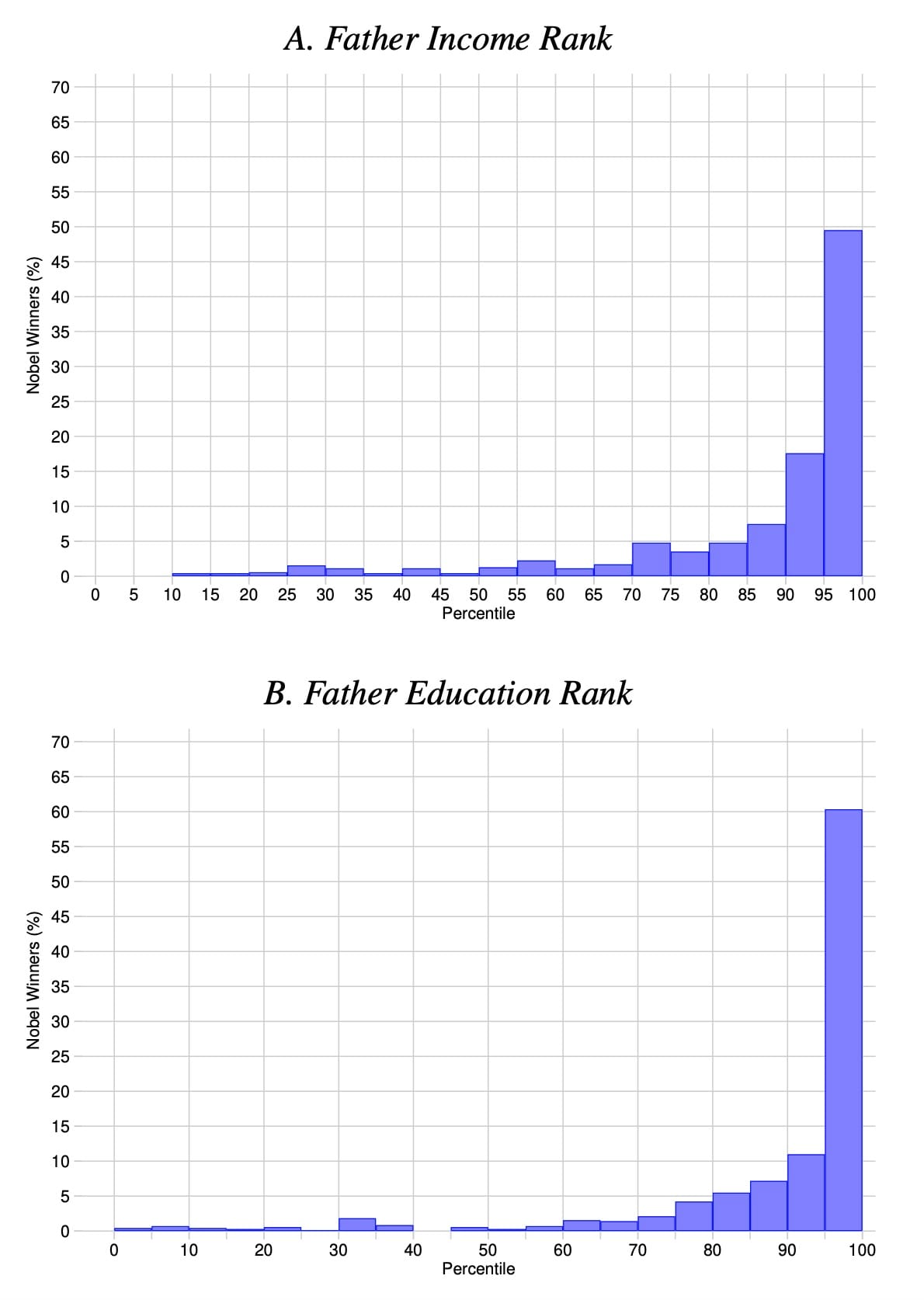

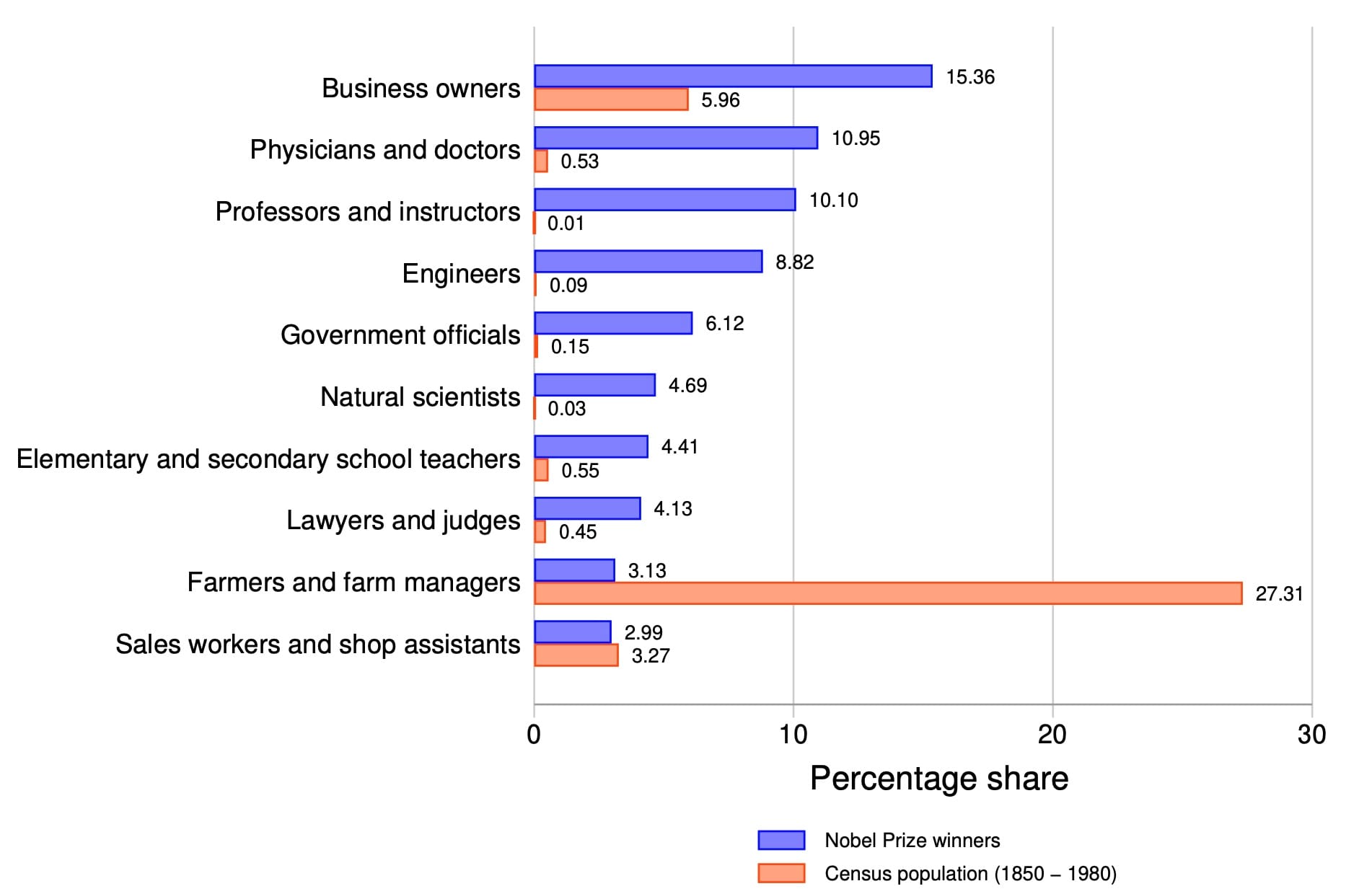

The article seeks to test these hypotheses by studying Nobel laureates (excluding the non-scientific Peace and Literature prizes). Unsurprisingly, most laureates come from very wealthy and well-educated families. The average laureate’s father is in the 87th percentile for income (earning more than 86% of the population) and the 90th percentile for education (having more education than 89% of the population). Moreover, over half of the laureates come from the top 5% of families. For women, the situation is even more striking—the average female laureate’s father is in the 91st percentile for income.

One positive trend, however, is that over the 120-year history of the prize, the average income percentile of laureates has decreased from 92 to 85. In other words, the proportion of families whose children could realistically aspire to win a Nobel Prize has nearly doubled over this period.

Academic Genealogy

The second article in today’s review[2] explores the topic of academic genealogy. When a young researcher earns their degree, they are mentored by a supervisor, who in turn had their own mentor, and so on. These academic lineages are well-documented and, in some cases, stretch back centuries.

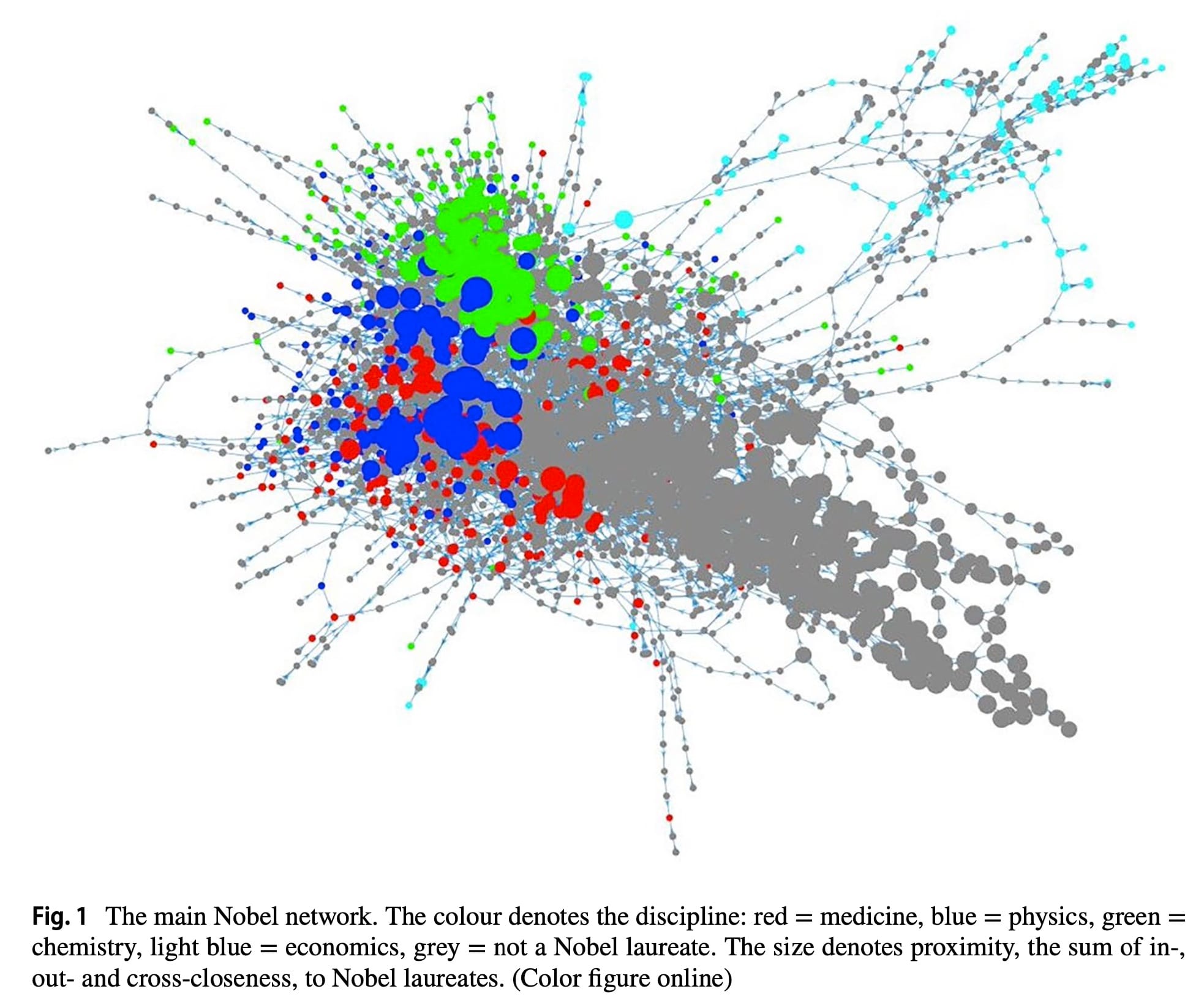

This article again focuses only on laureates in physics, chemistry, medicine, and economics. It turns out that among the 727 laureates, there are 25 family trees with a single Nobelist, 4 trees with 2 Nobelists, and 1 tree with 696 Nobelists. This is a remarkable agglomeration of excellence. Below is an image of this enormous genealogical tree.

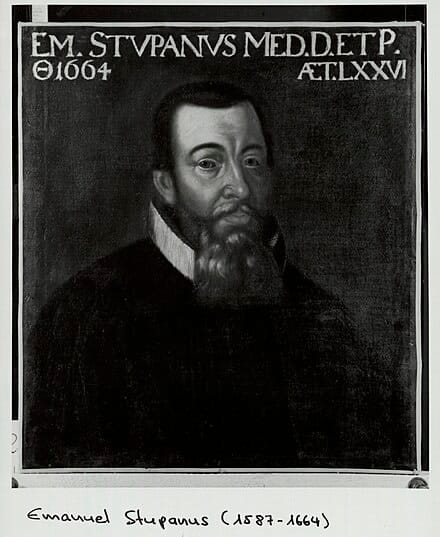

The common ancestor of 668 laureates in this tree is Emmanuel Stupanus, a Swiss physician who lived from 1587 to 1664 in Basel. His students, and their students in turn, went on to teach future generations of chemists, physicists, and biologists, many of whom began receiving Nobel Prizes in the 20th century.

How should we interpret this result? Does it imply that all natural sciences have their roots in early modern Europe? Are scientists from other regions of the world not receiving enough recognition? Or does global science represent a unified and interconnected structure, as seen in this massive tree? Without further research, it’s difficult to provide a definitive answer.

Conclusion

The Nobel Prize is often subject to valid criticism—ranging from doubts about the fairness of awarding certain individuals (or, as we witnessed in 2024, AI) to fundamental concerns about the feasibility of assigning individual recognition in an era of industrialized science, where thousands of people contribute to research. However, despite these critiques, many still hold the mistaken belief that science is an egalitarian field of human endeavor, free of borders, biases, and other such idealizations.

In reality, to have a strong chance of winning a Nobel Prize, you are likely to have been born into a wealthy family, received the right education, and formed "academic family" ties with other Nobel laureates.

References:

[1] Novosad, P., Asher, S., Farquharson, C., & Iljazi, E. (2024). Access to Opportunity in the Sciences: Evidence from the Nobel Laureates.

[2] Tol, R.S.J. The Nobel family. Scientometrics 129, 1329–1346 (2024).

Comments ()